Understanding the LME Warehouse Problem

Sometimes the perspective of history only allows us to understand a trend or a cycle when it is almost over. Such is the case with the recent case of the aluminum ingot premium bubble and the related LME warehouse queues. Sometimes we can learn a lesson from history, sometimes not. We have been preaching the dangers of these warehouse manipulations for years now and are penning this blog in the hope that this is a case from which we can learn some valuable lessons.

Sometimes the perspective of history only allows us to understand a trend or a cycle when it is almost over. Such is the case with the recent case of the aluminum ingot premium bubble and the related LME warehouse queues. Sometimes we can learn a lesson from history, sometimes not. We have been preaching the dangers of these warehouse manipulations for years now and are penning this blog in the hope that this is a case from which we can learn some valuable lessons.

The condensed version of this story is as follows:

The financial crisis of 2008 caused a rapid fourfold increase in LME aluminum stocks to almost 5 million tons. To profit from this surge, Metro ITS of Detroit built and acquired many warehouses and offered incentives to owners of metal to deliver to, and store in these warehouses under long term storage contracts. Metro quickly discovered that once inside the warehouses the metal stayed put. LME minimum out-loading rates were low, being designed for the traditional small warehouses of earlier times, and anyone who wanted to chase a cheaper storage deal by moving their metal had to cancel their warrants and join a queue. With control over their out-loading rates Metro had acquired a very profitable rental income stream.

By 2011 several banks and traders, big holders of warrants and shippers of metal had begun to understand, from dealing with Metro, the power over metal that came from owning large warehouses, so banks and traders themselves acquired several warehousing companies in the US, Europe and Asia, in a short span of months. These traders and banks also realized that as owners of both metal and warehouses they could lock up metal in queues and so cut off buyers from any spot metal in LME warehouses, which had always been the competitive supply of last resort in determining the published spot ingot premiums to which consumers’ global supply contracts were linked – US Mid-West, Rotterdam and Major Japanese Ports.

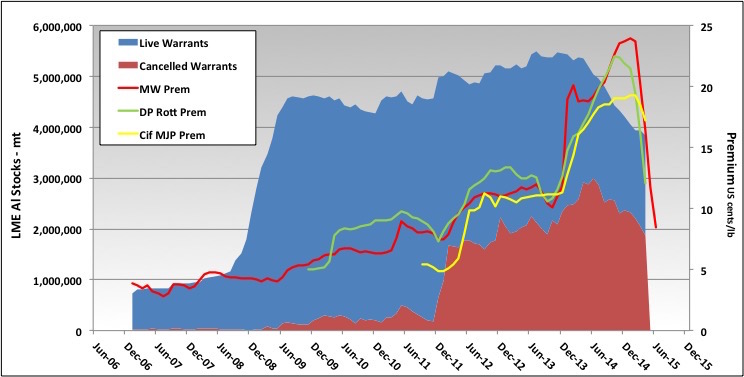

Once the banks and traders realized they could push up the premiums by depriving the market of LME spot metal by a stroke of a pen, they went to town. Between October 2011 and May 2014, a time of surplus when overall LME stocks were rising and traders clearly did not need LME metal for legitimate customer needs, they cancelled close to 3 Million tons of LME warrants. At a time when aluminum metal should have been freely available these mass cancellations created artificial queues of metal awaiting a loading slot to well over a year in Detroit. Similar actions in other regions began to have a spill over impact in metals like copper and zinc as well, compounding the problem. In the US, the absence of available spot aluminum caused by this manipulation pushed the Mid-West Premium from an already bloated 8 cents/lb to a high of 24 cents in early 2015. The full cost of this manipulation for US consumers of aluminum alone – ultimately the general public – has been estimated at $4 Billion over 2011-15

Meanwhile the LME, which regulated the warehouses and needed to maintain a legitimate spot pricing mechanism, acted at first in a way which others have accused of being weak in restraining these manipulations, and later was prevented by a UK court order requested by Rusal, from changing its loading rules for warehouses. Finally in November 2014 the order was lifted on an appeal by the LME, and in February 2015 the LME implemented stringent new rules to force warehouse owners into higher load-out rates. By this time the banks had sold their warehouse operations to other traders, leaving most of the LME aluminum warehouse capacity in trader hands. From February 2015 the Mid-West premium collapsed to around 8 cents/lb by end-June, close to its traditional range. This chart tells the story.

This “game” is obviously now over – for a while – but traders and financiers still own most of the metal and the warehouses which the industry depends on to create a close relationship between the prices that producers actually receive and consumers actually pay for spot metal, and the LME Cash Settlement Price, the still globally recognized price discovery and hedging mechanism for aluminum and other non-ferrous metals. The industry and the exchange must be vigilant to ensure that those who own a lot of the chips and nearly all the gaming tables do not in the future, as they did in the recent past, rig the game for the rest of the players.

David Waite – July 24, 2015

Permanent Link